Part 1: Global Health Under Pressure: Prioritizing Universal Health Coverage

![[Translate to English:] [Translate to English:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/4/5/csm_Design_ohne_Titel__1__4ddd4ec132.webp)

In our article series "Global Health Under Pressure," we examine the effects of U.S. funding cuts in development cooperation and changes in global health architecture on key issues in global health. We speak with experts from academia, politics, and international cooperation. In today’s contribution, the focus is on Universal Health Coverage (UHC).

Universal Health Coverage (UHC) aims to provide all people with equal access to appropriate quality health services without causing financial hardship.¹ UHC is a central goal of the 2030 Agenda and is enshrined in SDG Target 3.8. Outbreaks of HIV/AIDS, COVID-19, and Ebola have made us realize what it means when this access is not granted and how important resilient health systems are. When health systems lack funding to achieve UHC, the most vulnerable populations suffer. Despite this, healthcare and UHC are not a global priority at the moment. Political developments in the U.S. are even obstructing global health justice. In light of these challenges, it is encouraging that South Africa, during its G20 presidency, has prominently placed UHC and Primary Health Care (PHC) on the G20 health agenda. The question, however, is how UHC can remain a priority and be sustainably funded in the long term, especially in politically uncertain times for global health.

Health for All? Why Universal Health Coverage (UHC) and Primary Health Care (PHC) Are Vital for Global Health

"Ideally, we should live in a world where everyone has access to the essential health services they need, but this goal is still far from being achieved. Success will be a gradual process, freeing people from health-related poverty,"

Currently, more than half of the world’s population does not have sufficient access to essential health services, and about two billion people face out-of-pocket health expenditures that can drive them into financial ruin.²

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), UHC means that "all people and communities receive the health services they need (e.g., the full range of health services from health promotion, prevention, treatment, rehabilitation, and palliative care throughout the life course), of sufficient quality to be effective, while ensuring that the use of these services does not result in financial hardship for the users." UHC encompasses three dimensions: the population covered, the health services provided, and the costs covered. Approximately 90% of the interventions essential for achieving UHC can be delivered through primary health care.

In the 1978 Alma-Ata Declaration, the WHO declared health a fundamental human right and presented primary health care (PHC) as a central tool for achieving it. PHC is easily accessible close to where people live. It is provided on an outpatient basis, meaning it is not offered in long-term hospital settings but through general practitioners or community health centers. Alongside secondary or inpatient care and tertiary rehabilitation, it forms the foundation of health services.³

Primary health services directly save lives, as Marwin Meier explains. He is a political advisor on health and migration at World Vision, with over 20 years of experience in health across various civil society organizations. Initially, he worked for ADRA (Adventist Development and Relief Agency) as country director in Togo and the Philippines. Later, he joined World Vision, focusing first on HIV/AIDS and then on maternal and child health. Through primary health services, mosquito nets are distributed to protect vulnerable populations from malaria. However, during the COVID-19 pandemic, lockdowns in many countries prevented the distribution of nets, and some health centers were closed, reports Marwin Meier. According to the WHO, malaria infections increased by 14 million in 2020, reaching a total of 241 million cases, with the number of deaths rising to 627,000. A reliable universal health coverage system is therefore essential.⁴ Reliable universal health coverage is therefore essential.

UHC: Where Do We Want to Be by 2030?

UHC is part of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) set by the international community to be achieved by 2030, with UHC outlined in target 3.8. This includes financial protection, access to high-quality basic health services, and access to medications and vaccines that are effective, safe, and of high quality but still affordable.

Sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) are also an integral part of universal health coverage. Dr. Magda Robalo, former Minister of Health of Guinea-Bissau, now co-chair of the UHC2030 Steering Committee, interim executive director of Women in Global Health, and president and co-founder of the Institute for Global Health and Development, has been working on improving access to basic health services and addressing the vulnerability of disadvantaged populations throughout her career. In an interview, she explains why gender-responsive UHC is necessary. Women form the foundation of health systems. Globally, 70% of all health personnel are women, and 90% of nurses are female.⁵ „Therefore, there is no way we can achieve UHC if the needs, the contributions and the leadership of women is not taken into account, in ways that benefits the population. If you don’t take into consideration the needs [and contributions] of women in health facilities in your health system […] you miss opportunities of learning, because [women] know best how to [care for] mothers, children and pregnant women. You miss in your leadership and management the knowledge, experience and the [caregiving skills] of people who constitute the majority of the global health [workforce],“ says Dr. Magda Robalo.

However, we are still far from achieving gender-responsive UHC. One reason is the lack of data. "Women are made invisible," criticizes Dr. Robalo. Indeed, health data is still not consistently disaggregated by sex. This means that data for men and women is not presented separately. During the COVID-19 pandemic, around 60% of countries worldwide reported that they did not disaggregate their data by biological sex. This has devastating consequences: For a long time, it was assumed that biological sex made no difference in physical health other than size and reproductive functions, and so the biologically male body was considered the norm in medicine.⁶ Due to the lack of studies, medications are still often dosed according to the biologically male norm – too high for biologically female bodies.

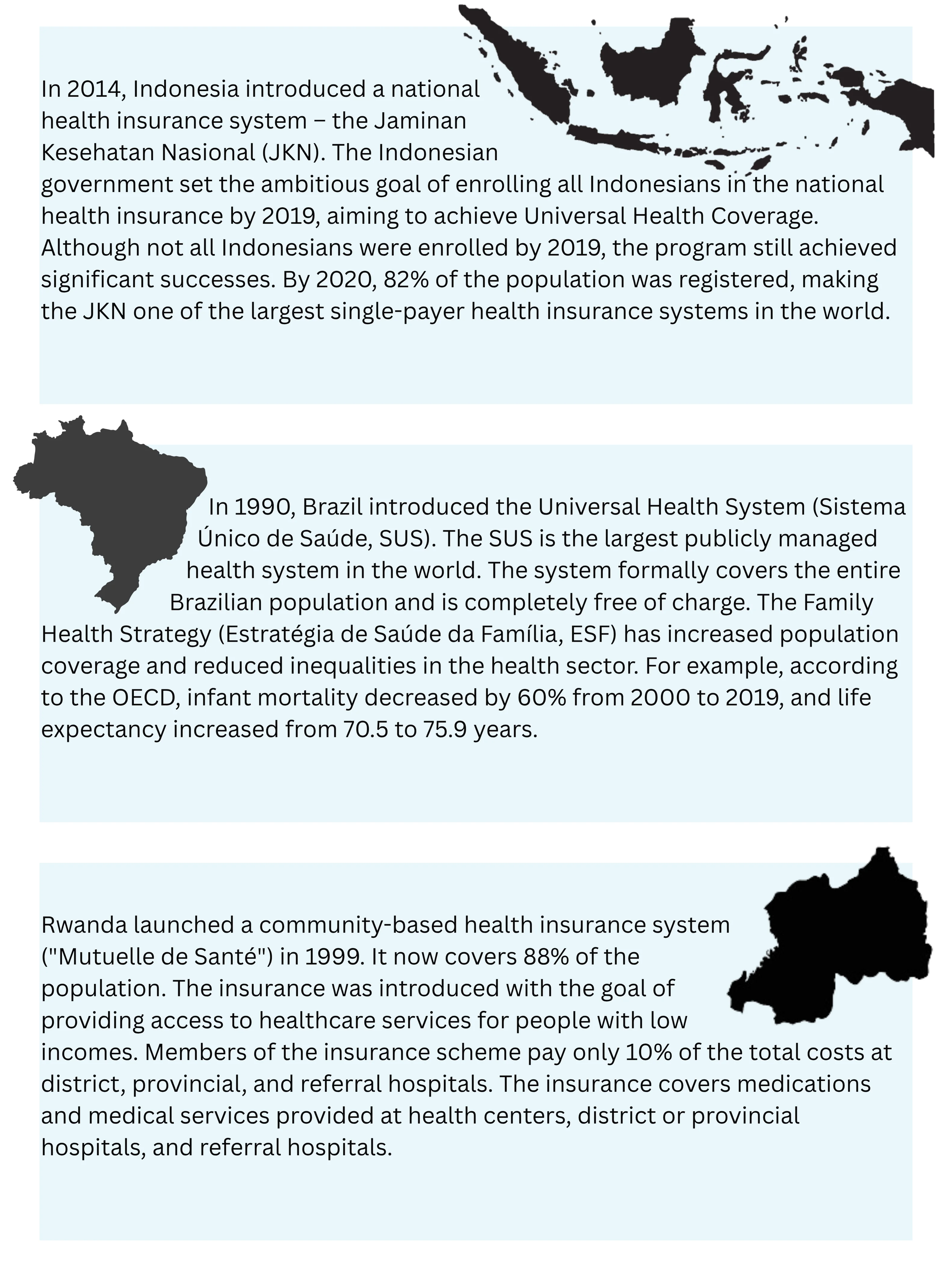

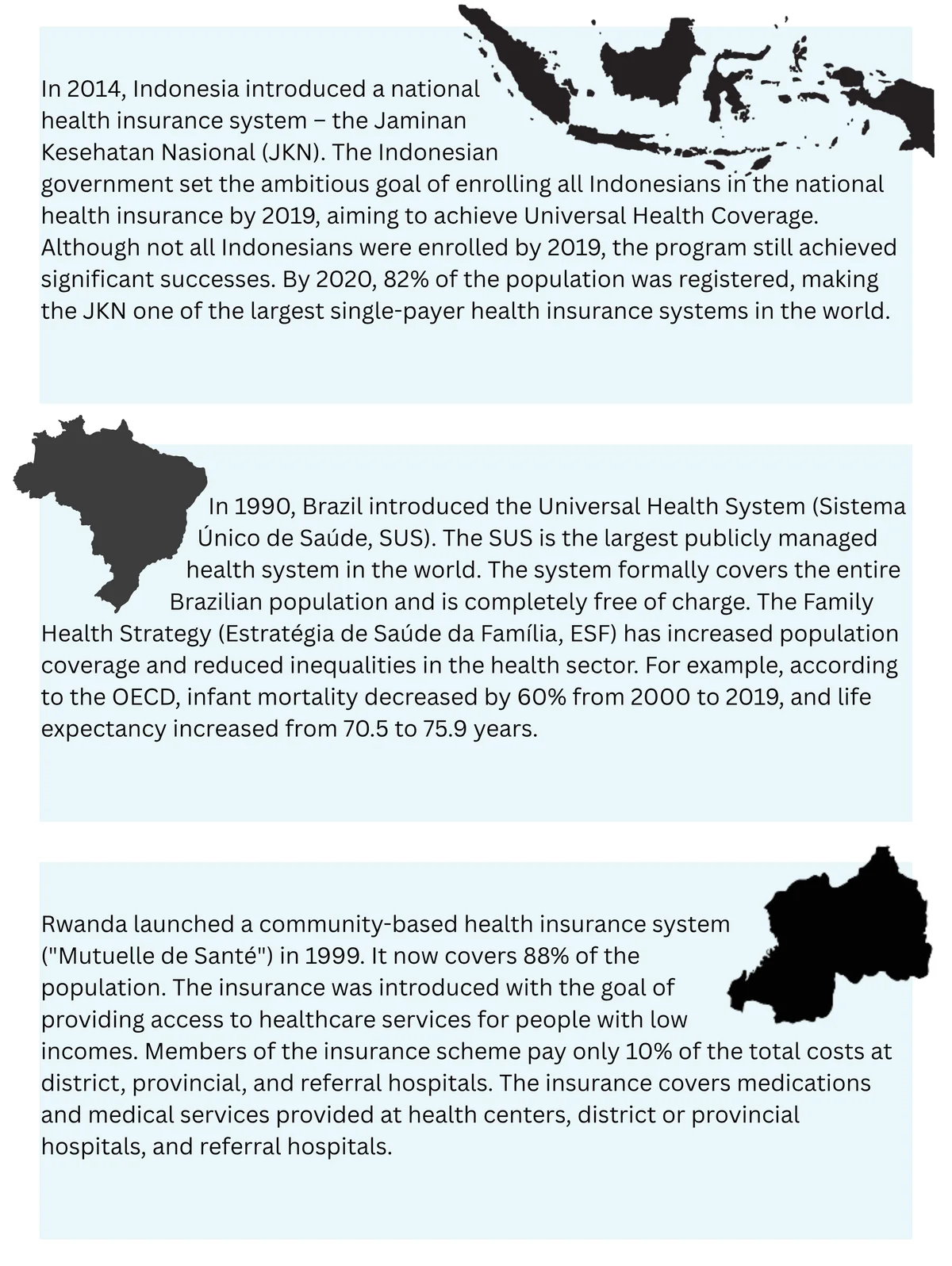

Another important indicator for achieving UHC is drastically reducing excessive household spending on health relative to income and total household expenditure. One possible strategy to make health services affordable for all is well-functioning health insurance systems. In an interview, Dr. Magda Robalo explains that the establishment and expansion of health insurance is a long-term task for states that requires careful planning. Regulations like the choice of service providers, the coverage of family members and the calculation of contributions are an essential prerequisite for reliable health insurance systems, but according to Dr. Robalo, many countries are struggling with this aspect. However, Indonesia is a positive example of implementing an effective health insurance system. Marwin Meier also names Brazil as a positive example of a well-functioning universal health insurance system. In Africa, Rwanda is a pioneer in universal health coverage.

The financial protection of individuals within a health system must go hand in hand with infrastructure development, according to Dr. Magda Robalo: "In order for people to contribute, they must receive the services they need." Because if a country offers a health insurance system but, for example, no medications are available in pharmacies, people will not pay for it.

Impact of U.S. Aid Cuts on UHC

The expansion of UHC requires substantial financial resources. According to an analysis by the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington, approximately 32% of global health funding comes from the U.S. Estimates suggest that U.S. financial resources will decrease by nine to ten billion USD in the next fiscal year and by 30 to 40 billion USD in the next three to five years.⁷

This is expected to result in significant setbacks in the fight against infectious diseases. The WHO predicts 15 million new malaria cases and 107,000 deaths this year alone, as well as an additional 3 million deaths from HIV/AIDS by 2030.⁸ When HIV/AIDS medications become unavailable due to shortages, patients die without treatment after four to five years, explains Marwin Meier. "Healthcare is a matter of life and death," he reminds us. The future of the fight against HIV/AIDS is insecure. The approval of the U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) expired in March, although the US Congress has approved funding until the end of September through a continuation resolution. However, the actual disbursement remains uncertain. The Washington Post reports that health services across Africa, according to Angeli Achrekar, deputy executive director of the Joint UN Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), continue to be interrupted. Countries such as Haiti, Kenya, and Nigeria are particularly affected, with their stocks of antiretroviral medications close to running out. Angeli Achrekar reports that in Kenya, after the initial payment stop, around 41,500 healthcare workers and community health workers funded by PEPFAR lost their jobs. By the end of March, only 11,000 had been rehired.

World Vision is also affected by the U.S. funding cuts. The organization occasionally distributes medicines and administers vaccines, but this is very rare, so they are not expected to face a supply gap. This may be different when it comes to human resources –also an important component of primary health services. World Vision works primarily in implementation and trains community health workers. Worldwide, 120,000 people work as community health workers and volunteer health assistants in communities for World Vision. These projects are planned and implemented by World Vision in close cooperation with local civil society and in coordination with governments in the project countries. They have long durations, up to 20 years, providing more security and predictability than shorter projects.

¹٫² WHO (2025): Universal health coverage (UHC). https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/universal-health-coverage-(uhc)

³ Vgl. WHO (2018): Primary health care: closing the gap between public health and primary care through integration. Technical Series on Primary Health Care. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/326458/WHO-HIS-SDS-2018.49-eng.pdf?sequence=1

⁴ Pharmazeutische Zeitung (2021): Tausende mehr Malaria-Tote wegen Corona-Pandemie. www.pharmazeutische-zeitung.de/tausende-mehr-malaria-tote-wegen-corona-pandemie-130101/

⁵ Women in Global Health (2020): Positionspapier Frauen in Gesundheitsberufen. globalhealth.charite.de/fileadmin/user_upload/microsites/ohne_AZ/m_cc11/globalhealth/Dokumente/WGHG_Position_Papers/WGH-GER_Positionspapier_Frauen_in_Gesundheitsberufen.pdf

⁶ Epstein, S. (2008). Inclusion: The politics of difference in medical research. University of Chicago Press; Perez, C. C. (2019). Invisible women: Data bias in a world designed for men. Abrams.

⁷ Science (2025): Trump has blown a massive hole in global health funding—and no one can fill it. www.science.org/content/article/trump-has-blown-massive-hole-global-health-funding-and-no-one-can-fill-it

⁸ Merkur (2025): WHO-Chef befürchtet Millionen Tote durch US-Förderstopp. www.merkur.de/politik/who-chef-befuerchtet-millionen-tote-durch-us-foerderstopp-zr-93631958.html

Related Articles